What makes habits durable?

I stopped writing this newsletter regularly. As a forcing function to restart, I reflect on what makes good habits durable

After consistently writing this newsletter for the last two years, I stopped. It’s not that I stopped writing. I read and wrote every single day, just not anything for Performonks.

As you know, I moved to Amazon a year ago. There, we communicate ideas and strategies, even financials, through Word documents, not PowerPoint. So that’s what I have been reading and writing daily - Amazon work stuff. And in all of this, my nightly writing ritual took a backseat.

A bad habit took its place. I replaced the soft glow of satisfaction from 30+ hours of writing each edition with the hit of dopamine every 15 seconds from an endless scroll of Reels.

In my attempt to crawl my way back into my old writing rituals, I thought I would explore what makes good habits durable.

First, I was curious to learn if we can measure durability.

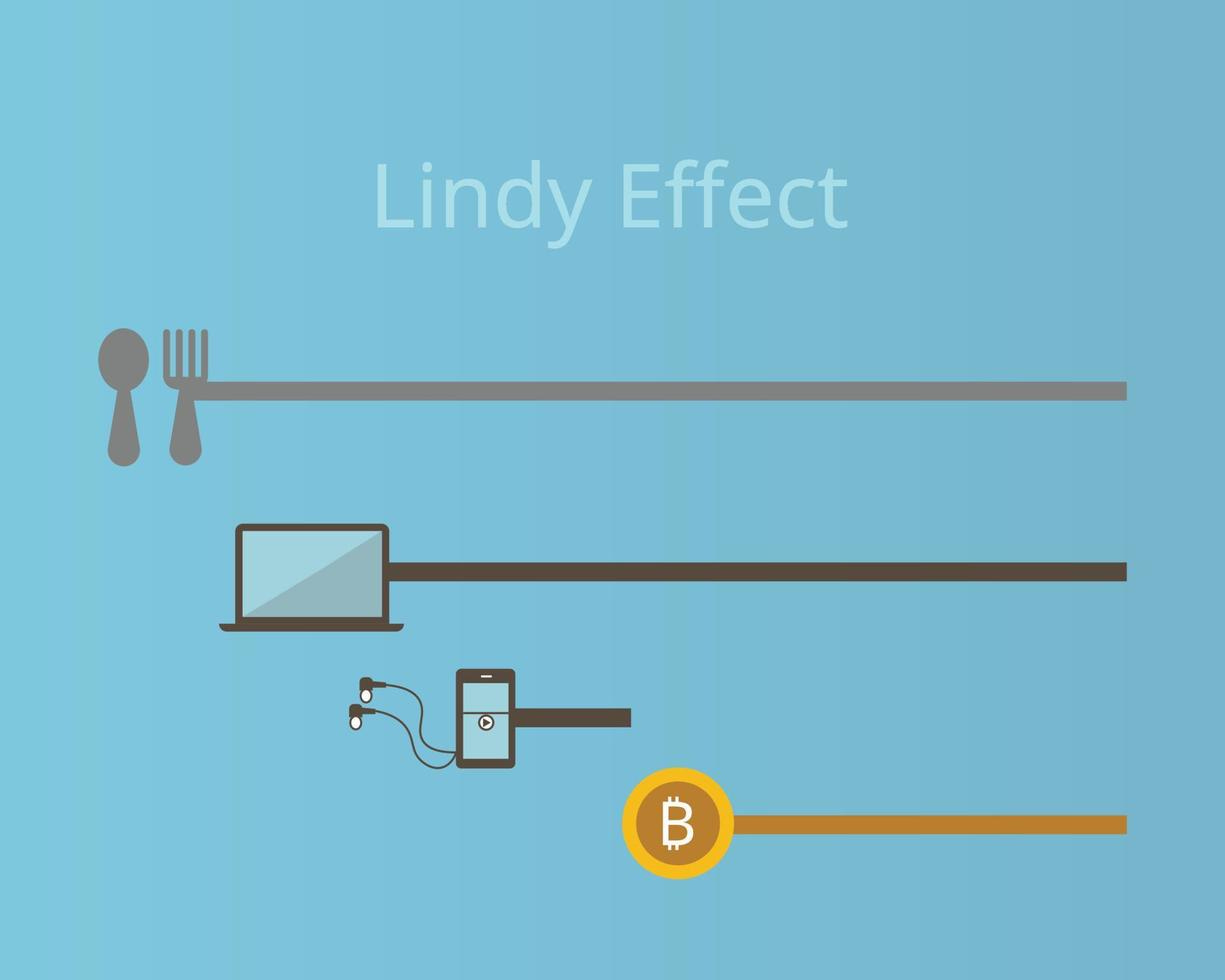

Lindy effect measures and predicts durability

The Lindy effect is a heuristic that predicts the longevity of nonperishables like ideas, books, jokes, songs, or inventions. It means that if something has been around for a long time, it is durable and, therefore, will likely be around in the future too.

The Lindy effect predicts that the future lifespan will be at least as long as its past life.

For Example, we have been singing “Happy Birthday to You” since the 19th Century, so it is very likely that we will continue to do so for at least two more centuries.

“If a book has been in print for forty years, I can expect it to be in print for another forty years. But,[…], if it survives another decade, then it will be expected to be in print another fifty years.”

Nassim Nicholas Taleb, in his book, Antifragile

The most common application of the Lindy effect is to help us sieve the chaff of information from the wheat of knowledge. We are better off choosing a nutritious diet of timeless books and articles over the junk food of daily news.

Lindy uses the rearview mirror to forecast longevity.

But how do we ensure that what we build new today also endures in the future? Habits for instance? Is there a formula we can apply to make our good habits durable?

Today, we will uncover what makes good habits durable.

What do sticky habits look and feel like?

Why do bad habits keep coming back?

What tiny habit hacks can get us back on track if we slip?

1. What do sticky habits look and feel like?

Sticky habits work on autopilot

A habit is hard-wired into our life when our body and brain execute it on auto-pilot. It’s like when we take the same route to work every morning without even knowing we took that particular route. Or when we brush our teeth or reach for that morning cup of tea without thinking about it.

When our muscle memory and unconscious brain take over, it’s good because then we don’t get a chance to get lazy or reassess what we are doing. The minute we start consciously thinking about whether to do something tough or not, we invariably ‘decide’ against it. We tell ourselves it’s too cold, or too warm, we don’t have enough time, or we will ‘do it tomorrow’.

I remember, when I started missing my 7 AM workouts, my trainer used to tell me to “just get to the gym without thinking about it.” I never made it to the gym if I allowed my brain even a nanosecond to ‘think’ about getting out of bed on a chilly Delhi winter morning.

2. Why do bad habits keep coming back?

Bad habits keep coming back because of three reasons.

2.1. They fulfill underlying needs

We can abandon habits but not our needs. Bad habits are just mechanisms we adopt to fulfil our needs. For example, if we crave deep friendships, we may fill the boredom with junk food or binge-watching TV.

Tony Robbins talks about six fundamental human needs. Each of these is easier to fulfil with bad habits than good ones:

Certainty — The need to be safe, secure, and stable. We won't care about healthy long-term habits if we do not feel stable and secure. If I knew I would die next week, I would not touch a morsel of healthy food! The corollary to this is that a true habit is what you would continue even if you knew you would die next week.

Variety — The need for change and excitement. This is where social media and Netflix addiction come in.

Significance — The need for achievement and importance. We want to feel like we matter. For some of us, trolling folks on Twitter (X) makes us feel important and superior.

Connection & Love — The need for human affection and friendship. We choose social media likes, shares, and followers instead of forging deep, meaningful offline friendships that take time to build.

Growth — The need to become better, faster, and stronger. We may think we are growing and learning if we are doing better than our colleagues, when in fact, the only good habit we need to nurture is to compete against how good we were the day before.

Spirituality — The need to feel like our life has purpose and meaning. We obsessively chase promotions and pats on the back at work, and that becomes our meaning.

Oftentimes, we replace a bad habit with yet another. A chain smoker might be able to give up smoking but might start to binge eat instead. A better idea is to substitute a bad habit with a good one that meets the same underlying need. A smoker could replace the chemical high from smoking with the adrenaline rush of three quick burpees.

2.2. We fail to manage our environment

Our environment contributes to our habits. We can set it up to enable good or bad habits that fulfil our underlying needs.

The famous rat park experiment is a great example of this. A population of rats was split into two groups. Rats in the first group were isolated in individual cages, with zero social contact and no toys. The second group was in a “Disneyland for rats”-lots of food, toys, and other rats to socialize with.

Both groups had two water dispensers - one with pure water and one with heroin-laced water.

The isolated rats' basic needs were not met, so they quickly became addicted to heroin water. On the other hand, the rats in the Disney park preferred pure water over the other!

The experiment did not end here. To prove the impact of environment beyond doubt, when a random sample of the isolated rats were moved to the Disney park, they started preferring pure water, too.

2.3. We fall victim to restraint bias

We have an inflated sense of self-control. So we expose ourselves to junky bad habits and believe that we can control our addictions.

We can’t.

This experiment proved it.

Northwestern University psychologists asked a group of smokers to take a ‘pretend’ self-control test. Randomly, half the group was told they tested high on self-control, and the other half was told they had low self-control.

Participants were then challenged to watch a 95-minute film, Coffee and Cigarettes, without smoking. They were asked to choose out of four temptation levels- they could (i) keep a cigarette unlit in their mouths (highest cash reward), (ii) unlit in their hand, (iii) on a nearby desk, or (iv) in another room (lowest cash reward).

Smokers who were told they had high self-control picked the highest temptation level, thinking they would be able to resist. Of course, they failed and lit up a cigarette on average three times more than the other group.

3. What tiny habit hacks can get us back on track if we slip?

We are all aware of James Clears’ Atomic Habits and B.J. Foggs’ Tiny Habits.

Their advice can be distilled into four practical hacks. These hacks manage our underlying needs and environment while removing our self-restraint bias.

Make each habit super-tiny: to get started, scale down a habit until it’s super-tiny. If I want to write a ~1,400 word newsletter, I could start by writing a 280-character tweet—or even one sentence, but daily. The point is to make the start as effortless and painless as possible so that we can stick with it. Slowly, we automatically start doing a little bit more - one sentence becomes one paragraph, and so on. When I know I need to get back into a regular workout habit, all I do is wear my workout clothes first thing in the morning. This effortless action makes me ‘feel’ fitter and gets me into the workout mind state.

Stack habits into daily routines: We all follow daily routines on autopilot. A very easy hack is to schedule the new habit right after an already sticky habit in our existing routine. This helps me understand why I fell off the writing wagon. My writing habit followed my nightly post-dinner routine, which was disrupted due to night work calls.

Replace, don’t stop a bad habit: stopping something is tougher than replacing it with something better. If we are used to eating something sweet after every meal, we are better off replacing that cake with a piece of Mejdool Date - a healthier way to satisfy a sweet craving. My social media screen replaced the laptop screen each night. Maybe one way I can start writing again is to replace the social media app with the substack app on the phone itself!

Fake enjoyment till we feel it: Much like Pavlov’s dog, when we reward ourselves after completing a new habit, we start craving the reward, and therefore, we start looking forward to the habit itself. The reward could be very simple. For me, it is a guilt-free breakfast after a good workout. While I was writing, the environment I created was a reward in itself. Soft light from the lamp, the same playlist on loop, green tea, and a little table on which I balanced my laptop. But as I changed cities, I could not recreate that same rewarding feeling, and I fell into the social media rabbit hole.

How will I start writing again? By just starting. Because I know that the only thing worse than stopping is never starting again.

See you in the next edition!