Moats, Trojan Horses and Flywheels

I discuss three mental models that indicate competitive advantage. Moats, Trojan Horses and Flywheels. And conclude that the Jim Collins' Flywheels model works best.

Ideas that help marketers master brand strategy and career growth. Performonks goes to 3,900 readers every week - subscribe here. Find The India Playbook here.

Warfare-inspired mental models

The mental models we use to describe competitive advantage in business borrow from the world of warfare.

Castles used to have deep ditches all around the periphery. These moats, filled with water and scary beasts like crocodiles, made the castle impossible to conquer.

"Moats" in the context of business mean exactly what they meant for castles. They are inherent strengths, entry barriers, and competencies that make a business impenetrable to competition.

Warren Buffet was the first to apply this concept to business. He says, "The key to investing is [. . .] determining the competitive advantage of any given company and, above all, the durability of that advantage. The products or services that have wide, sustainable moats around them are the ones that deliver rewards to investors."

A brief overview of moats

The stronger the company, the deeper the moat. Moats for both traditional and new-age companies are largely of four types:

Scale

Brand

Assets and Capabilities

Network Effects

Scale: Scale offers the biggest (pun intended) moat.

Scale takes time to build and requires heavy investment in assets like production plants, truck fleets, warehouses, and factory workers. For instance, the strongest moat for FMCG companies is their distribution strength, which takes years to build.

All companies born during and after the Industrial Age—newspaper publishing, Car manufacturers, Oil and gas, FMCG, Computers, and Hotels—have scale as a moat.

New-age companies like Google, Facebook, Amazon, and Apple started with tech innovation as their moat. But over time, their scale has also become their moat.

Brand: The deeper the trust a brand enjoys, the stronger the moat.

Brands that become habits are strong moats. A Coke drinker might not switch to Pepsi, and an iOS user might not easily switch to Android.

Assets and Capabilities: Inherent competencies become moats.

The knowledge capital and thought leadership that firms like McKinsey, Bain, or Ideo bring to the table are not easy to replicate because they are embedded into the soft capital and culture.

The DNA of luxury businesses is artistic mastery. They develop exclusive, high-quality products in limited quantities, which allows them to charge astronomical prices.

Network Effects: When the utility of a product improves as more people join, it enjoys network effects.

Facebook, WhatsApp, or a telephone are of no use if people we want to connect with are not on there.

Trojan Horse made moats redundant

With time, people realized that innovation can disrupt fully formed moats. Brands like Dollar Shave Club, Nirma, and Fogg found an unmet niche and became Trojan Horses to big brand moats.

Elon Musk famously says, "Moats are lame. If your only defense against invading armies is a moat, you will not last long. What matters is the pace of innovation — that is the fundamental determinant of competitiveness.”

All this is great. But it feels incomplete to me.

Moat and Trojan Horse seem unidimensional, and they don't do justice to the complex system of interconnected parts that comprise each company. Because there is no silver bullet for invulnerable companies. Invulnerability comes from a series of interconnected actions that compound over time.

That’s where Flywheels come in - a non-warfare inspired mental model.

Flywheels and Jim Collins

Jim Collins gives us a third mental model in his book Good to Great - Flywheels.

Collins says, "Picture a huge, heavy flywheel — a massive metal disk mounted horizontally on an axle, about 30 feet in diameter, 2 feet thick, and weighing about 5,000 pounds. Now, imagine your task is to get the flywheel rotating on the axle as fast and long as possible.

Pushing with great effort, you get the flywheel to inch forward, moving almost imperceptibly at first. You keep pushing, and after two or three hours of persistent effort, you get the flywheel to complete one entire turn."

My simple definition of a flywheel is a series of strategies that work well together and compound results over time.

Eric Jorgenson breaks down flywheels into four elements, which I paraphrase here:

Momentum — Flywheels are huge objects. Getting a flywheel to move is hard. But once it gets moving, its own motion powers it to greater momentum with each turn.

Feedback Loops—With each turn, speed increases, which powers the next turn. In the same way, as success becomes visible, more people join in, making the journey easier.

Compounding Return on Effort —Successful flywheels compound success little -by little over time.

One Direction — Changing direction negates all efforts. So, all activities that make up a flywheel should necessarily move in the same direction.

Therefore, a good flywheel becomes an impenetrable moat over time.

Innovation is baked into most flywheels. Most strategies don’t start off as innovative. Instead, interconnections between strategies make a company system innovative.

Let's look at some flywheels.

Amazon

The most famous flywheel is that of Amazon.

A low-cost structure allows it to offer low prices to consumers —> which attracts more consumers —> which incentivizes more sellers to list products on Amazon —> which offers an even wider selection —> which gets even more consumers —> which further increases scale to command lower prices from sellers.

This flywheel is such a great example because it creates moats on all four axes:

Scale: Amazon is a Trillion-Dollar company by Market Cap. This is a deep and wide moat that makes entry by a new E-Commerce player almost impossible.

Brand: Amazon is the second most valuable brand globally as per Statista. [Source]

Assets and Capabilities: huge capital investments in technology, warehouses, and logistics, and zillions of data on shopper behavior.

Network Effects: more buyers, so more sellers and vice versa.

Disney

Great business leaders instinctively incorporate the flywheel into their thinking process. This is the flywheel Walt Disney drew even before he built his empire.

While the Amazon flywheel started with lower prices, the Disney flywheel is built on the power of the brand. It looks complex, but it can be summarized as follows: use success from the cartoons for merchandising and parks.

Air BnB

Air BnB's flywheel is built upon network effects and the belief that homeowners will open their homes to strangers in return for money.

More hosts attract more travelers, more travelers expand the market of hosts. This happy coexistence is facilitated by a trusted social proof mechanism (reviews and ratings).

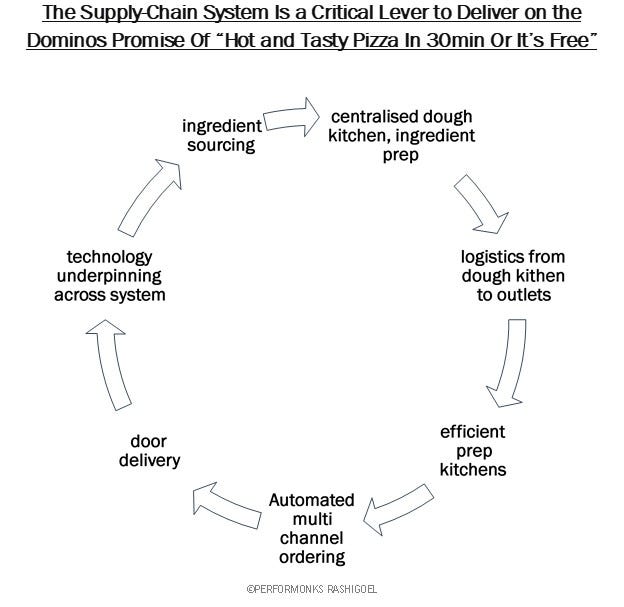

Dominoes Flywheel

Dominoes is not a pizza company but a technology and logistics company.

My takeout? Great companies are systems of interconnected parts that make up a strong, impenetrable fortress.

Thanks for reading, and I’ll see you next week!

I hope this post reaches more and more people. Surprised that this goldmine has no engagement.

Spotify and Uber are classic examples of this flywheel.

Uber -

Low prices -> attracts more consumers -> attracts more drivers -> demand supply match -> repeat

Spotify uses the Costco flywheel - economies of scale combined

Low prices -> attracts more consumers -> attracts more artists for monetisation -> increase in returns for Spotify -> use that capital to invest in enhancing user experience -> repeat!

Similar - ish flywheel for Netflix.

Flywheels can be used for content creation also. Something I pitch to my personal branding clients:

Post > comment > get noticed > build authority > repeat.