The ripening of the Influencer Economy

Influencing needs to be legitimized as a formal job. This will also be good for the country.

Ideas that help marketers do better and be better. Subscribe here. Check out my other essays on marketing here.

Welcome back to Performonks!

I shared a simple influencer marketing framework earlier. Find it here.

Since then, the more I think about it, the more influencer marketing reminds me of those crazy brawls we see in Asterix comics.

It's become a wild marketplace where gigabytes and eyeballs collide head-on.

Every consumer is hooked on content, hungry for the next dopamine high.

Countless influencers (I use influencers and creators interchangeably) are fatigued from content creation marathons that have no finish line.

Brands are all chasing after the same distracted consumers and popular influencers, making it a real mess.

In all of this, social media algorithms change on a dime and wipe out all the hard-earned followers, adding to the chaos.

And like all new industries, the economics are inefficient.

From the brand’s point of view, influencers demand upfront payments but are unable to always prove ROI. Methods like influencer-specific discount codes track results but are clunky and difficult to scale.

For influencers, it's no walk in the park either. Brand deals are one-off, high-maintenance, and involve administrative and legal coordination. Creators want to create, not drown in paperwork.

Only the social media platforms seem to be laughing all the way to the bank.

In my opinion, for the influencer economy to hit escape velocity, a few adjustments need to happen.

Influencing needs to be legitimized as a formal job. This will also be good for the country.

For this to happen, the average influencer and brand owner need to

Shift their mindset away from ‘bigger is better’, to thinking small - 1,000 true fans small.

The average influencer needs to get savvy about monetization. Right now, they are narrow-focused on monetizing attention through a B2B model. They need to build B2C pillars that focus on selling products and content.

Here goes.

Influencing needs to be legitimized

As is the case with any new industry, the power law holds - only 150k out of 80MM influencers make money. (Source: Kalaari Capital Report).

It will become a legitimate profession when not just the top 1%, but a majority of influencers start making enough money to sustain their livelihoods.

In fact, influencing needs to become so legitimate, that ‘Professional Influencer’ becomes an option in the job section on government forms.

This is not just an industry imperative, but also good for India.

Five reasons why.

We are a large country, made up of many many small numbers. We are many many people consuming a little bit. And this makes us very large, but only in the aggregate. We sell more sachets than shampoo bottles. We even sell half a bread alongside a full one. Our paan shops sell lose cigarettes alongside cutting chai and we must be the only nation in the world that sells 6 small Parle-G biscuits for Rs.5 by the billions daily.

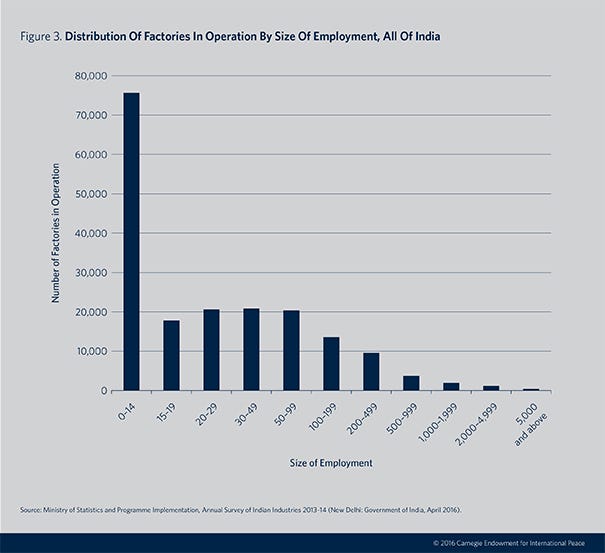

We are a nation of micropreneurs. Not just our consumer goods, but even our industry is made up of micro-enterprises earning micro incomes - for instance, this chart shows that a majority of our factories are small, with less than 14 employees.

We are the most populous nation, but we simply do not have enough jobs for 53% of our population that is under 30 years old. In fact, we have the lowest labour force participation rate in the world!

We are also a rag-tag economy of unorganized professionals. A study by the International Labor Organization shows that India has one of the world’s largest informal sectors. 83.6% of our population in the non-agricultural sector is engaged in informal businesses.

We are an unskilled population. One of the reasons we are an informal economy is that only 2% of our population is skilled (Economic Survey 2015). This is not just a problem, but a ticking time bomb.

This seems to be the perfect storm for the influencer industry. If many many influencers become many many micropreneurs and earn enough to sustain their livelihoods, not only will they thrive, but the nation will too.

How much would they need to earn? And is it even realistic?

I think so.

The power of many many small numbers also applies to incomes

$10 a day gives us a comfortable, middle-class livelihood. A globally accepted definition of the middle class is households that earn $10 a day (2011 PPP). Studies show that at $10, a household can not just live comfortably, but more importantly, is not vulnerable to slipping back into poverty during macroeconomic disruptions.

$10 a day is ~Rs.3 lakh per annum. (Rs.82=$1).

This more or less aligns with Rama Bijapurkar’s analysis (which I have found to be the most credible, as she uses government sources). I have shared it earlier, here. Her analysis shows that only the top 20% of Indian households make an average of ~Rs.3.94 lakh per annum. And these make up the middle class.

20% is only 62MM households.

As a country, should we not strive to get 80MM of our influencers to the middle-class level?

How will the math work?

1,000 True fans X Rs.394 per annum

Kevin Kelly wrote that even if an influencer has just 1,000 true fans who are willing to pay $100 a year, he or she can earn a comfortable livelihood. I have written about this here.

For India, we don’t need $100, we need Rs.394 ($4.80) per annum per fan.

Would you not pay Rs.394 per annum for an influencer you like?

Surely, in a country of 448 MM social media users, an influencer with even the most niche content would be able to find 1,000 true fans would they not?

Yes, they could. If they think like Kabir Chugh. He has strategically chosen an uncrowded niche- restaurants and entrepreneurship.

Scale becomes irrelevant if the model is correct. He has only 137k followers on Instagram and yet he made Rs.3.2 lakh ($39k) in his first year as an influencer by diversifying into courses and working with very very select brands.

See Kabir Chugh’s Insta page here.

How can we have many many influencers like Kabir Chugh? Maybe even 80MM of them?

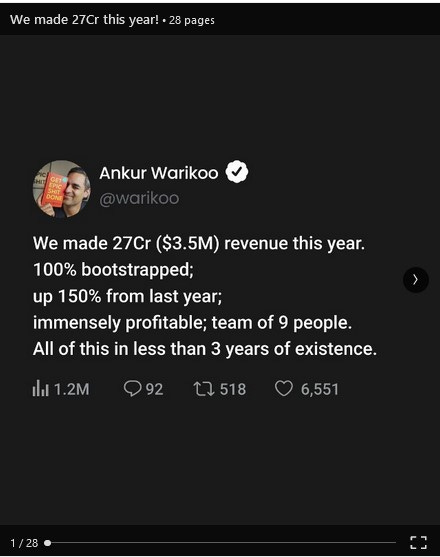

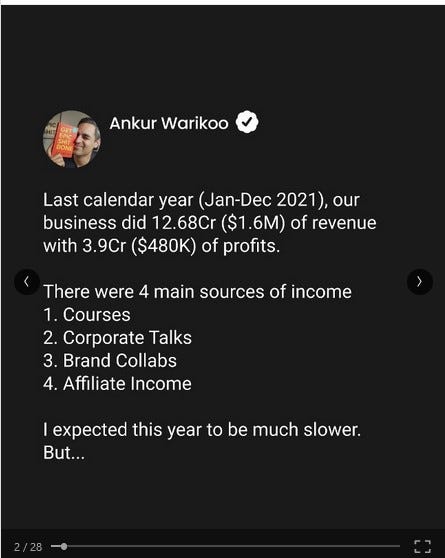

By losing the ‘bigger is better’ mindset. By not getting paralyzed by the success of super influencers like Ankur Warikoo, who made Rs.27cr ($3.29MM) as a creatorpreneur in 2023. See the full post on his income breakup.

And you know what gives me hope that it might be possible to have millions of Kabirs and maybe 1% of them will be the future Ankurs? That both Ankur Warikoo and Kabir Chugh’s playbooks are the same.

They didn’t just monetize attention via a B2B model - ad revenue sharing (with platforms) and brand endorsements+affiliate fees (with brands).

Instead, they have diversified into a B2C model of selling content (books, courses) directly to consumers.

Today there are many platforms that enable direct B2C monetization of content. Subscriptions, courses, books, coaching, patronage - Gumroad, Ko.fi, Substack, Knackit, Teachable, Maven, Patreon and so on.

But what about monetizing products?

That’s happening too.

In the product economy, influencers are becoming brand owners and curators

There are two models to monetize via the product economy.

Brand owners: Kim Kardashian has 363 MM followers on Instagram and she has successfully built SKIMS into a $500MM revenue brand (2022). But again, I want to show you how even with a much smaller follower base and a niche promise, an influencer can build a respectable brand and earn more than a decent living.

Food vlogger Madhura Bachal’s niche is Marathi cuisine. She launched Marathi spices and she says these spices contribute more to her annual income than revenue from branded content.

There are many more examples across beauty (Wearified, featured in Vogue), Apparel, and even accessories (Snobshop sells accessories and has only 11.5k fans on Insta).

The beauty of the internet is that influencers now come in all shapes and sizes. Even all ages. My favourite creatorpreneur is Nanaji. Nanaji is 86 years old. As an Ayurveda aficionado, he owns 4,500 Ayurveda books. During the lockdown, he along with his 81-year-old wife, experimented and perfected an anti-hair fall oil for his daughter. The hair oil was so effective that the family started a business selling Nanaji’s Ayurvedic hair products. (I have also bought it because the reviews are great!). The business is funded by Amazon Smbhav Fund. They’ve also been on Shark Tank! And they have 517k followers on Instagram. Check out their website here.

Not everyone can produce products. That’s where the second model of the product economy comes in - curation.

Curation: We are seeking new brands and new products. That’s why most of our shopping trips start in the Amazon search bar. But there are also many D2C brands that are sprouting everywhere. We need a trusted voice to test and curate products for us.

Influencers who know their clout depends on the quality of their recommendations will be thoughtful and will excel at curation - they will become our tastemakers.

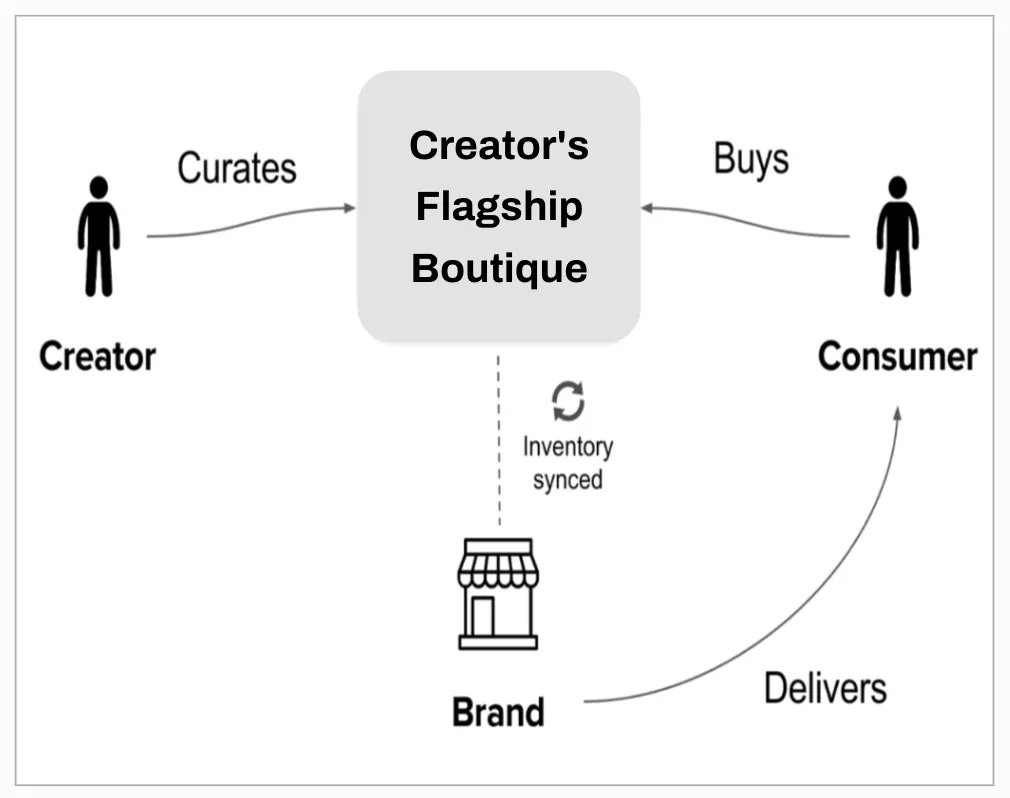

I recently came across a platform - Flagship. Not sure if something like this exists in India. Flagship is the Shopify for Influencers - it allows influencers to launch an online boutique. An influencer curates a selection of products and earns a commission, while the brand manages logistics.

I like this model because it removes operational complexity and middlemen and solves the needs of all three parties- Brand, Consumer, and Influencer.

This was the influencer part of the story.

It will help if brands shift their focus to small over large.

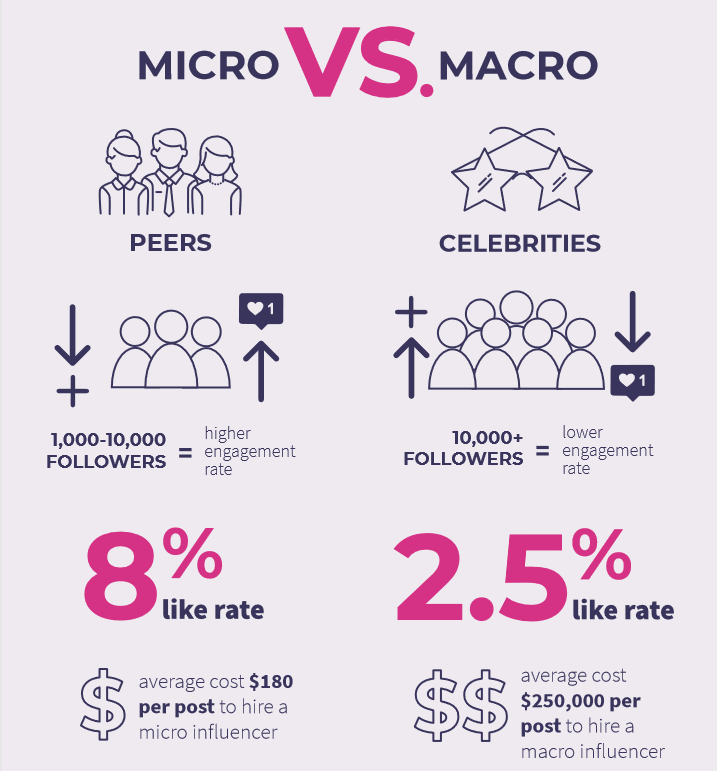

If brands prioritize engagement over the number of followers, they will be better off too. We know engagement and the number of followers are inversely related.

If instead of preferring mega and macro influencers, brands work with many many nano and micro-influencers, they will not only reach the same number of consumers in the aggregate but also achieve higher engagement. That’s good business because they will spend less too. Below is some rough math.

Naturally, an outcome of the micro-influencer focus will be a shift from English to Vinglish

Moving to micro-influencers will automatically deepen overall reach at the grassroots level. This again is good business because we know that a local bodybuilder who speaks Haryanvi will be able to build a better connection for the brand amongst youth in Haryana than Tiger Shroff.

And that’s exactly what Muscle Blaze has done. I follow Ankit Baiyanpuria as he works through the 75Hard challenge. He also happens to be a Muscleblaze endorser.

Thanks for reading. Let me know what you think about this thesis.

I would also be very keen to learn from you, the names of startups that you think are solving for this space.

Until next time!

“that a majority of our factories are small, with less than 14 employees”

Hello Rashi, the above line sums up the whole scene. Wonderful. Great job. Thanks for enlightening people like me who don’t read these kind of marketing stuff otherwise. Thanks again.