The India Playbook: The Sachet Economy

India contains multitudes and demands a fit-to-context playbook. I explore ten insights of the Indian market over ten emails. Part IV: The sachet economy

Newsletter on ideas that help marketers do better and be better. Subscribe here.

Over the next few weeks, you will receive ten emails from me. Each mail will decode one insight about India and what it means for business.

Part IV: The Sachet Economy

Whether you travel the dusty roads in a village far away from the city, pause to catch your breath in front of a tea shop on Shimla Mall Road, or walk up and down the back lanes of the Kalkaji market in South Delhi, you won’t escape the sight of curtains made of hundreds of sachets adorning kirana (grocery) shopfronts.

The average Indian has a cash flow problem - she does not have enough cash in hand at one time. So she consumes in bite-sized installments - at magic price points of 1, 2, 3, 5, and 10.

This makes India a ‘sachet economy’.

Everything here is ‘sachet-ised’ - shampoos, hair oils, even mobile phone data.

Magic price points work across categories - 70-75% of the shampoo market comprises sachets at Re.1 and Rs.2. (source). While 75% of the total biscuits category sits in the Rs.5 and Rs.10 price points. (source)

Most magic price points are one serve/one use - The Horlicks Rs.2 sachet makes one cup. Maggi Rs.5 makes one serve. One shampoo sachet washes one head of hair and so on.

The beauty of the sachet economy is that it works across high-value categories also, through old strategies like EMI and new ones like Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL) in e-commerce.

In an attempt to get more credit card usage, even credit card companies have resorted to giving us the option to convert our credit card payments into EMIs.

Making, transporting, and selling (not to mention advertising and retail margins costs) a small number of sachets at a time and charging only Re.1/2 is not profitable.

That’s why, scale is essential.

The sachet economy only works at scale

The sachet model works at such wafer-thin profit margins that only when millions and billions of sachets are sold, do volume economies kick in.

Also, a portfolio of large and small packs builds a profitable business. (The more profitable unit economics of larger packs offset the lower profits from sachets).

That’s why, all successful brands maintain one brand but many prices.

One brand-many prices

Take a look at Airtel and Parle G. Both maintain their magic price points for their categories - Rs.10/20 for Talktime and Rs.3/5/10/20 for biscuits.

The only difference is the entry price point - Rs.10 for telecom but only Rs.3 for biscuits and the highest price point - Rs.2,000 for telecom and only Rs.80 for biscuits - that’s because there is a limit to the number of biscuits one person can or wants to eat, but data has now become oxygen.

Multiple packs: Now what complicates the market even further is that the Rs.3/- pack is not exclusively purchased only by the less affluent consumer. Even the super-rich buy it for multiple reasons. They might like the taste and want to portion control. They may buy it for the poor kids on the street, or for their grandmother who has a habit of eating two Parle Gs every evening with her tea. That’s why ParleG also sells a bundle of twenty Rs.3/- packs.

This way, one brand is able to cater to all Indians while also building one brand equity that travels up and down all four Indias.

The importance of television: Since sachets are mainly sold through the wholesale channel, television advertising becomes important to build brand awareness and signal quality. Without this kind of social proof, the cash-poor consumer sticks to their tried and tested brands only.

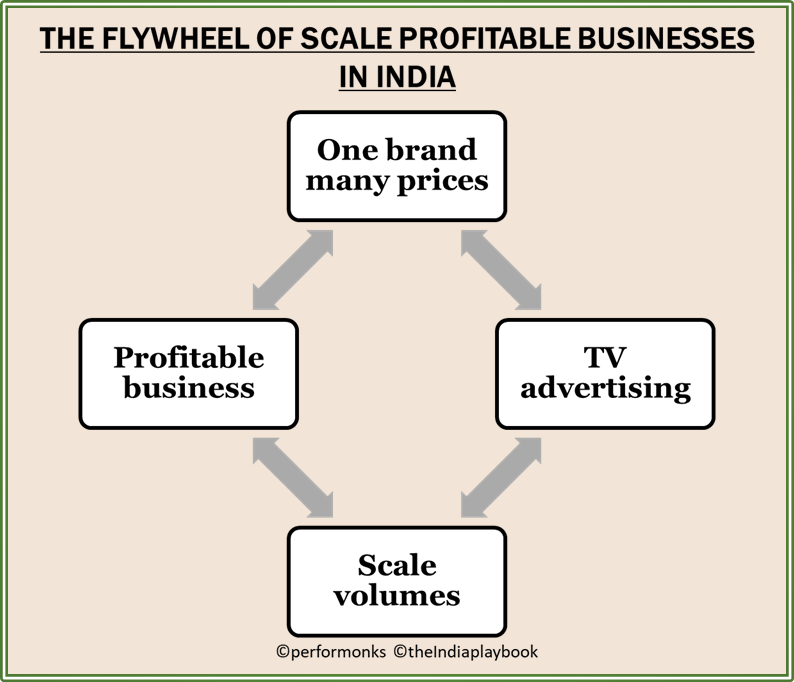

In a nutshell, there’s a flywheel of profitable scale businesses at work here. A portfolio of different price points helps balance profitability, drives scale, and generates enough cash to pay for television advertising, which in turn generates enough consumer demand to enable the business to make and sell billions of sachets each year.

Which brings me to the story of PepsiCo’s Lehar Iron Chusti. Many people gave many hours to this noble cause. But it failed to take off because we never activated this flywheel.

Lehar Iron Chusti

The year was 2009. I was tasked with building a BoP (Base of the Pyramid) business by selling iron-fortified biscuits and snacks for teen girls in poor districts of Andhra Pradesh.

Our research showed that teen girls only have Re.1/- or Rs.2/- to buy snacks and treats after school. So we had to price our biscuits and a snack at Rs.2/-.

Since we only focussed on the less affluent population it did not make sense to launch a range at higher price points.

The flywheel never kicked in. We never scaled enough to make the business worthwhile for PepsiCo.

It’s true when they say failure teaches us more than success.

Thanks for reading.

Poll

Now that you have read 4/10 of The India Playbook. I have a question for you.