The 10,000 hour rule (Part I)

10,000 hours, the donkey rule and the importance of deliberate practice

Ideas that help marketers do better and be better. Subscribe here. Check out my other essays on marketing here.

We like neat and straightforward formulas to navigate life’s complexity, so we can blame the formulas if we don’t succeed.

One such formula popularized by Malcolm Gladwell in Outliers was, “If one puts in 10,000 hours of practice, one can achieve mastery”.

I myself shared this idea in an earlier newsletter-Metamorphmagus, where I proposed that we can prolong our career by stacking new skills alongside our existing skill set by following the 10,000-hour rule.

In response to this newsletter, one Performonks reader wrote to me and asked,

“In your experience, what is the length of a cycle to learn new skills? And how do you phase these? For example ppl working in Marketing who then have an interest to go to Sales later in their career do an hyphen shaped move (breath) which develops them into an I (depth) over time. Over a period of time, a combed shaped skillset will be acquired.

Hence, it really comes down to short term vs long-term thinking. Very strategic.

I have always tried to optimize my skill building towards interest and curiosity vs strategy. By when should one try to be more strategic with the choices to make and how does one do it better?”

Her questions kept echoing in my mind… and the more I thought about it, I realized that in focusing on the 10,000-hour rule, I had ignored ‘The Donkey Rule’ - Even if a donkey got 10,000 race hours under its belt, it wouldn’t be able to beat an Arabian race horse!

The Donkey Rule

Which means that we have to be thoughtful about choosing what to practice. Simply practicing any skill will not get us to mastery if we are not wired for it.

10,000 hours of practice for a naturally talented person works like oxygen that turns a flame into a burning bonfire!

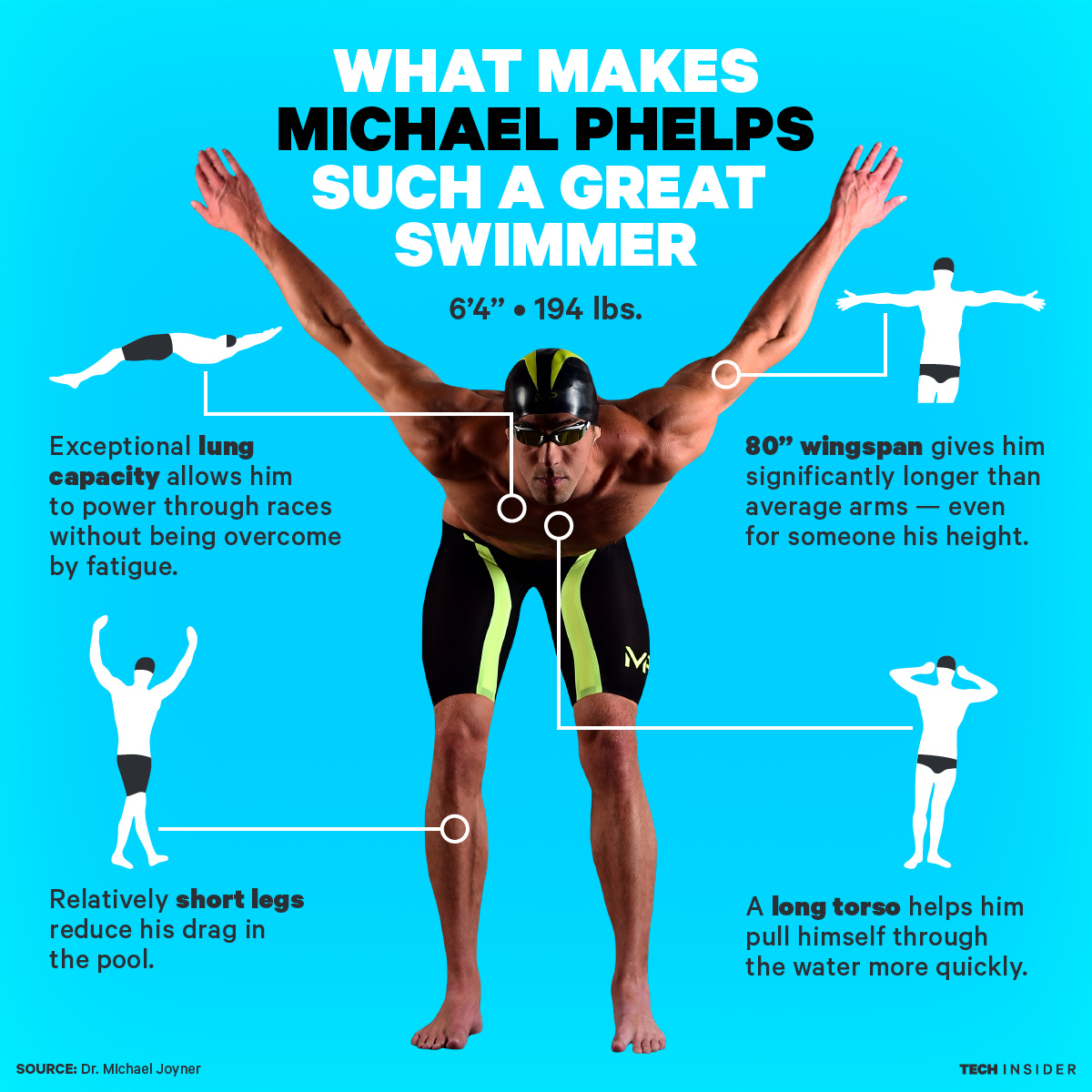

When nature was programming the set of genes that would come to be known as Michael Phelps, it was probably in a hurry and left a few bugs in the code.

These bugs became features that made Michael Phelps a world-class swimmer.

His broad chest can push through water with force.

His relatively shorter legs create less drag effect when in motion.

His wingspan is longer than the average human, so each stroke pushes him further.

Double-jointed ankles give his kick unusual range.

Even his body chemistry is unique. His body produces half the lactic acid of a typical athlete —since lactic acid causes fatigue, he can push his body harder.

But these natural advantages could have been lost forever, had he chosen to pursue… let’s say… PhD in library sciences in The Blah University of Library Sciences. Or if he had decided to spend his days inhaling burgers while Netflix and chillin’.

Instead, he put in not just 10,000, but hundreds and thousands of practice hours.

In 2016, Droga 5 made this goose-bumpy campaign for Under Armour that showed the exacting practice, single-mindedness, and pain that went into making Michael Phelps a 22-time Olympic Gold Medal winner.

Two lessons here in the context of the ‘Donkey Rule’.

pay attention to your natural gifts and advantages - find that Arabian horse within yourself

once you find it, go hell for leather to practice practice, practice, and practice

While luck may have played a role here (picking swimming as a career instead of library sciences), one cannot discount the quality of practice.

All Practice Isn’t Equal

Two marathon runners with the same height, muscle mass, and nutrition follow the same training schedule. But still one of them does better than the other. The difference is how deliberately they practice.

Deliberate Practice: means consistent practice with mindful intent that helps us get better each time. It means watching ourselves in action, identifying what we can do better, and then correcting ourselves.

The famous violinist Nathan Milstein wrote:

Once when I became concerned because others around me practiced all day long, I asked [my mentor] Professor Auer how many hours I should practice, and he said, ‘It really doesn’t matter how long. If you practice with your fingers, no amount is enough. If you practice with your head, two hours is plenty.’

Practicing with our head in the game is deliberate practice. Performing the actions mechanically is like a lion roaring in the forest and no one there to hear it.

The US Navy does this well. Studies show that Navy pilots who trained even during peacetime against more seasoned colleagues and then analyzed their training runs improved their combat performance ten-fold.

They know that without deliberate practice, the benefits of practice plateau fast.

Coaching: High-quality practice also involves getting a teacher or expert to watch us in action and throw light on our blind spots.

I had shared the example of Atul Gawande in an earlier newsletter. Atul is a top surgeon. At the height of his career, he requested his professor to observe him while performing surgery and then deliberately worked on his weak areas. Even a surgeon of his caliber had blind spots - his elbow position, how the overhead light was placed etc.

“That one twenty-minute discussion gave me more to consider and work on than I’d had in the past five years,” says Gawande.

Visualization is surprisingly powerful: Doing something is good. But visualizing in addition to doing is even better. Mental practice is remarkably effective in getting us to mastery.

A study of golfers found that novice golfers who combined mental practice with physical practice performed better than those who only did physical practice.

So if we visualize ourselves in action - performing the skill we want to get better at, we might cut down on our practice time.

Emotional Involvement: “Leave emotions out of it,” is bad advice. Emotions play a critical role in learning. In an NYT article, Dr. Immordino-Yang discusses that “it is literally neurobiologically impossible to think deeply about things that you don’t care about.”

The emotion that drives us to learn better is rooted in curiosity and a pull for the material rather than the push of fear. Probably that is why I don’t remember much of subjects like civics or Hindi I studied in school, because I studied out of fear of failing the exam, not out of curiosity.

Dr. Yang says that curiosity is the most fertile learning state. She says curiosity is a “nuanced, implicit and emotional process” during which “you’re open, you’re safe, you’re in a kind of intellectually playful place in which you’re sort of exploring possibilities.”

The lesson here is to build skills that we have an interest in and feel genuine curiosity about. If B2B marketing does not excite you, if you don’t look forward to reading the manual on international audit practices, stop torturing yourself and find a different skill you are curious about.

My marketer friend who wrote to me said they err on the side of curiosity and interest. So they are already on the right track. Here is the TL: DR until now:-

pay attention to your natural gifts and advantages - find that Arabian horse within yourself

and once you find it, go hell for leather to practice practice practice hard

practice deliberately - mindfully watch yourself while practicing

you may already be performing tasks that are skill-adjacent - again, be mindful to embed them as strengths

get a teacher to point out blind spots

visualize practicing skills

and focus on what you find interesting and feel curious about

If we practice deliberately, we can become comb-shaped or pi-shaped even as we go about our day job. This is because even though our main job might be marketing, we perform tasks that are skill adjacent. We develop growth forecasts, we negotiate costs and timelines, we try to inspire and motivate our teams and we resolve barriers. All these skills can easily prepare us for an adjacent career, for instance, sales.

If we become more deliberate in the work that comes our way, we build mastery. For this, it is important for us to get off the tick-off-the-to-do-list treadmill in our heads and be more mindful.

How could we be strategic about skill stacking? Let’s leave that for Part II, shall we?