Stories are self-fulfilling prophesies (Part I)

If we change our personal story, we can change the arc of our life

A newsletter on mental models to help marketers do better and be better. If you like it, you can subscribe.

This is the first edition of a two-part series on personal storytelling.

Our shape-shifting autobiography

At some point in our lives, we have all shared our personal histories with others.

When we do that, we don’t realise that each time we share our story, we play a game of Chinese whispers with ourselves.

With each narration, even without realising it, we move a few facts around, shift the meaning slightly, and end up creating a new memory (of our story) for ourselves.

The next time we tell our story, we build on this memory. This way, over multiple years and numerous narrations, the story we end up with differs from the one we started with.

So, which version of the story is the right one?

What remains constant? Do the facts that change even matter?

Is what we have forgotten even important? Or is it a blind spot?

Through these two essays in the series, I make the point that

If we change the autobiography in our head, we can change the story we write next.

Why?

Because we are the sum-total of all the stories we believe about ourselves.

Two narrative arcs

Northwestern University psychologist Dan McAdams has developed a concept he calls “narrative identity.” He defines it as “an internalized story you create about yourself — your own personal myth”.

Like myths, our narrative identity is made up of heroes, villains, keystone events, and the adversities we have overcome.

McAdams studied narrative identity for over 30 years and concluded that all narratives boil down to two story arcs - Redemptive or Contamination stories.

Redemptive stories transition from bad to good. People who tell such stories are more likely to be motivated to give back to society and nurture future generations. These people are able to find a gift, a learning or a positive outcome even in the most dire of circumstances.

Contamination stories transition towards bad. Such people tend to be more anxious and depressive. They are unable to find meaning in their lives and, hence, tend to think less about giving back to society.

His research proves that stories we tell ourselves have a domino effect. And just by changing our contamination story to a redemptive one, we can increase not just our happiness levels, but our whole lives.

This video best illustrates this concept. It’s a must-watch.

In this video, an inadvertent mistake changed the way this person thought about himself. And just this one thing changed his life trajectory.

We would think that getting grades is a small event and life is made up of tragic setbacks and disasters. Once can’t possibly give a redemptive spin to those. But Viktor Frankl proves that it can be done.

Viktor Frankl’s personal story arc

He suffered inhuman levels of torture in the Nazi concentration camp. He could have (justifiably) contaminated his story and focused only on the (very real) suffering all around him.

But instead, he identified a purpose for his life and immersed himself in it. That made all the difference between living and surviving with grace vs. perishing, broken and beaten.

In this edition, I will discuss how we might consciously rewrite our story to make it more ‘redemptive’ in a three-step process:

Step 1: Realize there is no one truth - The Rashomon Effect

Step 2: Find the themes

Step 3: Flip the script

Next week, I will discuss ideas to protect our redemptive stories from contamination.

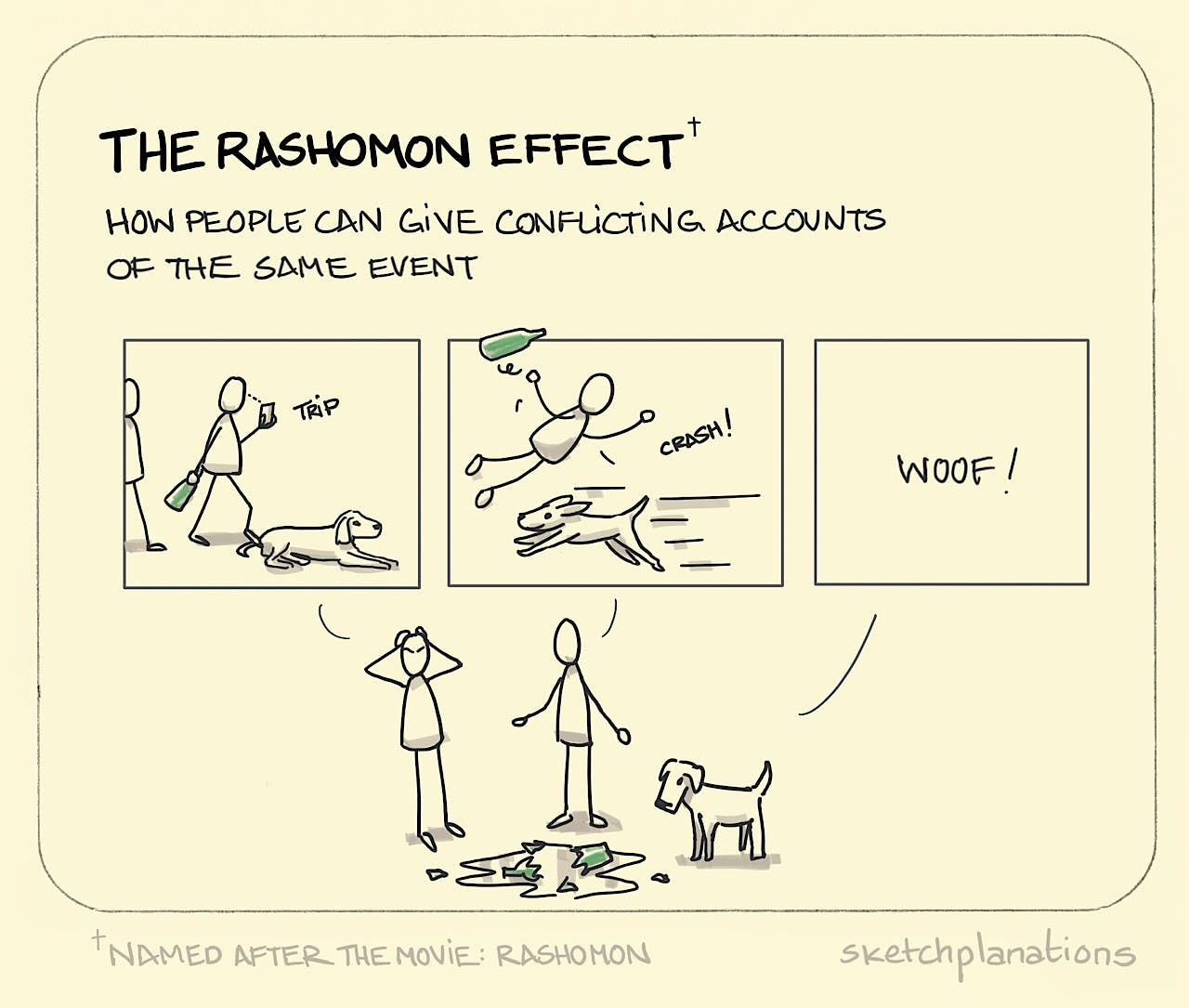

Step 1: Realize there is no one truth - The Rashomon Effect

Oftentimes, we forget that we are not the only participants in our story. There are as many versions of our story as there are people.

Rashomon is a first-of-its-kind thriller directed by Akira Kurosawa. The film begins with the murder of a samurai in a forest. Then, all the characters - a monk, the wife, a bandit and the samurai (in spirit form), share their versions of the murder.

Each version is subjective, self-serving, contradictory and even manipulative.

The Rashomon effect is named after the film.

In the same way, different versions of our life stories exist, i.e. we are all unreliable narrators of our own lives.

And our narration is unconscious. To retell our life story with a redemptive lens, first, we have to become conscious of the story we tell about ourselves. Here is how we could go about it:

First,

Pretend you are recording your autobiography. Pick any medium that you find easy.

record a personal podcast video.

write your story in novel form. Let each chapter cover five years of your life. (If you are 40, your novel will have 8 chapters).

Only you will read or watch this, so be as long-winded and detailed as possible. No censoring is allowed.

Second,

Notice key milestones and experiences that have been especially painful or joyful. Double down on those and dig deeper -

what gave you joy?

what gave you pain?

what was happening there that made you feel a certain way?

are there default patterns of behaviour that you fall into - both good and bad?

Third,

Activate the Rashomon effect - get versions of these key milestones from different people.

Limit to trusted friends and family. They will rarely have poor intent, but their versions of our story will throw up many blind spots.

Make sure you discuss your life and the key events in the third person. This will help in two ways. First, it will encourage family and friends to open up and speak frankly. Second, it will help us take an objective view of our story.

A good way to do this is to pretend to be a podcast host and interview friends and family. It’s important to record the interview so you can reflect on it later.

This will be important for us for Step 2.

Step 2: Find the themes

The sum is greater than the parts. Through this exercise, we identify our victories, innate strengths and crystallize the themes we have lived.

Look for blind spots and pleasant surprises

Once we start processing all the data we have collected, themes will reveal themselves to us like lightning flashes.

We can further process our story by asking ourselves, ‘Why did we do it that way?’, ‘How did it make us feel?’, ‘What happened?’, and ‘Why did we feel that way?’

For instance, we might remember the experience of having a very strict math teacher as transformative because the high standards might have driven us towards excellence. If we see a pattern of such examples, we could conclude that challenges spur us on. That is an autobiographical theme.

Look for themes that have remained constant

Themes stay with us throughout our life.

For instance, look at Grandma Moses. Her story shows that the most innocuous events end up becoming themes. She had wanted to paint since she was a child. She recollects, “I was along about 9 years old when my father said one morning at the breakfast table, ‘Anna Mary, I had a dream about you last night.’ ‘What did you dream, pa?’ ‘I was in a great, big hall and it was full of people. And you came walking toward me on the shoulders of men.’ As of now, I have often thought of that since.”

She lived her entire life as a farmer’s wife. Household duties kept her from painting. She finally took up painting at the ripe old age of 76 and achieved fame in a time when painters were mainly men.

Things that gave us joy when we were children are hints of what we are good at. Grandma Moses said, “[As a child] I used to like to make brilliant sunsets, and when my father would look at them and say: ‘Oh, not so bad,’ then I felt good. Because I wanted other people to be happy and gay at the things I painted with bright colours.”

It is easier to find positive themes. But what if we find themes that are not so positive? We flip them.

Step 3: Flip the script

We are the writers, editors, and raconteurs of our own stories.

Now that we have different versions of our story, we can make, as McAdams says, “narrative choices.”

This is not a deep emotional exercise but a simple edit job of combining all the best versions to craft the best version of our story. Remember, we are rewriting our story, not our emotions. As Eckhart Tolle says, “Emotion in itself is not unhappiness. Only emotion plus an unhappy story is unhappiness”.

We can actively flip our unhappy stories and only focus on the gifts we gained from them. For instance, I suffered from ill health in childhood, so I was not very physically fit and sporty. Instead of focusing on the sports experience I lost out on, I celebrated all the time I had to read fiction! And reading has become a lifelong gift from this phase.

Even making small story edits to our personal narratives can have a big impact on our lives.

Here are a few tips on how to rewrite our story:

Find the gift in the unfortunate events

Find our flow - what we were naturally good at, and enjoy

Notice opportunities that came easily

Notice victories and what led us to them

Notice people and relationships that gave us energy

Once we have flipped our story, even small tweaks toward a more redemptive story arc will make a world of difference.

Once we have done this, we will keep refining it for the rest of our lives.

But even more importantly, we have to protect it from ‘contaminating’ our story going forward.

That’s for the next edition.

Until then, stay inspired!