Dance the dance between standing out and blending in

When is blending in a good strategy and when does it become a malady of mediocrity? Like life, there is no failsafe formula - blending in and standing out fall along a continuum.

Ideas that help marketers be better so they can do better. Subscribe here. Check out my other essays on marketing here.

It was Valentine’s day and the year was 1996. My third and final year of college. It was an all-girl college but we all awaited Valentine’s Day with more butterflies in our collective stomachs than Graduation Day.

Every girl, even the ones who did not have a boyfriend, had resolved to bring her best-looking self to college. I also bought a new t-shirt, a beautiful neon green with a zipper. On D-day, I walked into campus only to merge into an undulating sea of neon green-clad bodies - a pride of Peahens preening for their real and imagined Peacocks.

Now I am no Miranda Priestly, but I attribute this neon-green throw-up to this dress Kajol wore in DDLJ. (released in Oct 1995, and was still running to packed theatres).

This was a mimetic desire at its best - we are hard-wired to want the same things and before we realize it, we find ourselves swimming in the sea of sameness.

For marketers, ‘sameness’ is a malady and we avoid it like the plague. But in doing so, we wrestle with a paradox - if we copy-paste from others we run the risk of commoditizing our product, but if we are too different, our product might be ahead of its time and fail.

This is also true in our personal and professional life. If we zag when others are zigging, we are labelled black sheep. If we are agreeable and mirror others, we blend into the background and are written off.

In an earlier edition, I had written that our brains have evolved to notice and respond to the new, while at the same time seeking comfort and continuity in the familiar.

That’s why marketers have to dance that age-old dance between blending in and standing out.

This leads us to wonder, in which situations is blending in a good strategy? And where does sameness become a malady of mediocrity?

Like life, there is no one failsafe formula - blending in and standing out fall along a continuum.

1. ‘Safe is not safe’ in ‘mating-like’ situations when a few (even just one) have to be chosen from many

Mating games are competitive. So are job interviews, fundraising, sports events, conferences or crowded shopping aisles. What stands out gets noticed.

That’s why brand merchandising at the point of sale is so critical to driving sales. Marketers who are reading this will know this sales tenet, “jo dikhta hai wohi bikta hai” (what you can see, sells). And that’s also why we invest time and money to dress for the job we want and differentiate our elevator speech, pitch deck or resume.

Theoretically, this strategy sounds correct but is challenging to execute unless we are a niche player or are in danger of getting disrupted.

1.1 Businesses wrestle with Clay Christensen’s Innovator’s Dilemma. New products generate revenue only over time, so companies get imprisoned by the baseline effect. For instance, Nestle India needs to add 6 Yoga Bar companies in one year to grow by 10%. So financially, they are better off allocating more resources to existing businesses instead of launching new disruptive product lines.

To protect the baseline, businesses launch incremental innovations or twists on copycat products, which then fail. Nielsen has been measuring breakthrough innovations for the last 11 years. They define breakthroughs based on 18-month performance. They found that on average, 14,000 new products are launched each year in India and only ~0.2% of them succeed. In 2012, only 23 out of 16,914 launches succeeded (Economic Times) - a 0.13% success rate. In 2022, only 15 new launches made it to the breakthrough innovation list.

1.2 I looked at the face wash category to illustrate what copycat innovation looks like. A search for ‘Face wash’ generates 20,000 results on Amazon, 3,055 on Nykaa and 21,505 on Flipkart. This makes sense. As horizontal marketplaces, Amazon and Flipkart want to offer as wide a selection as possible. While Nykaa, as a vertical store, curates its selection.

I analyze a subset of about 80 face wash products. A quick scan reveals the malady of sameness. 95% of the products are in tubes. All have a 4+ rating. All have colorful packaging (leaning towards green), while men’s face washes are 'manly’ in black. All drive incremental differences through smart wordplay (blemish free vs brightening, or anti-acne vs oily skin vs acne-prone skin), and through ingredient claims (saffron, lemon, neem, aloe, turmeric etc.). Nivea, with its teardrop bottle shape, does break out of the clutter for me.

When product innovation is dependent on ingredients, brands ride ingredient fads and are often unable to build sustainable and scalable revenue models.

As we know, sometimes an insurgent shakes the inertia out of a slothful category. The standout product for me, in this context was Minimalist - a new DTC brand. It breaks all the familiar category codes. A simple white, almost pharmaceutical type of bottle with scientific ingredients. This product looks effective and a consumer who wants a fairer complexion might just reconsider her face wash brand. For a two-year-old business, they seem to be doing well. They have raised INR1.1 billion from Sequoia and also have Unilever Ventures as investors.

1.3 Cars have been forced to break out of innovation inertia because of Tesla: No one wants to kill the golden goose. Car companies have been riding the fossil fuel economy for decades, and have not attempted to disrupt themselves.

Cars manufacturers seem hell-bent on looking similar. They differentiate through branding and last-mile service. They forget that branding alone cannot differentiate a me-too product beyond a point and last-mile service is replicable - so it may not remain a defensible moat for long.

The malady of sameness has crept into most aspects of their business. This is a picture of cars across price points, brands, and countries. But with brand names masked.

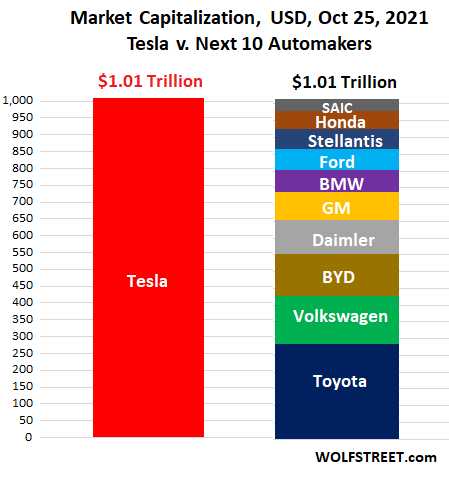

Until Tesla comes along. At its highest, Tesla’s market cap was equal to the combined market cap of ten car makers.

Technological innovations generally have a two to three-year head start. Tesla’s success has jolted traditional car companies into green tech and their new launches should level the playing field soon.

1.4 Cirque du Soleil dances this dance well. Cirque du Soleil has taken familiar circus-like elements and added world-class gymnastics, creativity, storytelling, emotion, and music to make it into an art form. They keep innovating and changing their acts to stay fresh and ahead of the curve.

2. ‘Same same but different’ to sustain continuity

In Greek mythology, Procrustes was a bandit who attacked people by stretching them or cutting off their legs, to force them to fit the size of an iron bed. Work and life are a little bit like that. Once we are ‘chosen’ out of many for the unique value only we can offer, we are pressured to blend into the culture and rules of the new place.

If we overplay our uniqueness, we rock the boat - 99% of people settle in and stop feeding their uniqueness. We are fearful because the nail that sticks out gets hammered in first. We are also afraid of overplaying our hand and failing. Over time, this fear cocoons us, we feel cozy and safe but our ‘uniqueness muscles’ atrophy.

Jeff Bezos calls this the Day 2 mentality.

“Day 2 is stasis. Followed by irrelevance. Followed by excruciating, painful decline. Followed by death. And that is why it is always Day 1.” — Jeff Bezos

1% stick their necks out opportunistically yet strategically to add differentiated value. Real leaders do this by owning and driving new organization-wide agendas that are also in tune with their inner convictions.

Don’t let the noise of other’s opinions drown out your own inner voice. —Steve Jobs

2.1 We think, in order to win in these situations, we have to be combative - like in a boxing tournament. The one with the more knockout punches will be the last person standing. I disagree. I think we win when we start to play as if we are part of a jazz band. We riff off of others - sometimes responding, sometimes retreating, sometimes leading. All this time also playing the instrument we are the best at.

Three leaders, in three similar companies, but with very different agendas come to mind. Paul Poleman’s visionary sustainability agenda. A.G Lafely’s focus on product innovation, and Indra Nooyi’s conviction in better-for-you products. All three built strong teams and were not directive despots, yet they retained and even sharpened the edges of their unique vision. In the end, they left their companies stronger and more durable.

Paul Poleman’s career especially demonstrates this principle of same-same but different. Paul Poleman was slated to be the CEO of Nestle worldwide, but Paul Bulcke was made CEO instead. So Unilever poached him to be their CEO. Before Nestle, he spent 26 years in P&G. Three companies with very different cultures - he enmeshed himself into each culture, yet managed to stand out and make an impact.

Two more examples come to mind. The Beatles and Bohemian Rhapsody.

2.2 Once we succeed in an environment, we allow ourselves to be imprisoned by our success, and we stop innovating. It is said that The Beatles would have never been such an extraordinary success had they continued to sing their early hits over and over again. They keep disrupting their sound - new themes, genres, unusual instruments, and recording techniques - and stayed fresh.

2.3 Bohemian Rhapsody does not blend into the rules of music-making. An unsaid rule of music creation is to make it repeatable - the same note, choruses, and refrains make sure listeners follow the song and hum along. Bohemian Rhapsody shattered the repeatability construct. The song has five musical sections, each with a different style - from a ballad to opera to rock. It works because it mirrors Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey. The hero’s adventure is triggered by a murder (‘Mama, I Just Killed a Man’). He accepts the call of adventure (‘Gotta leave you all behind and face the truth.’). His descent into the abyss, (‘I don’t want to die.’). And finally, rebirth (‘Anyway the wind blows.’).

3. ‘Hide in plain sight’ when survival is at stake

When situations are political, leaders choose legacy protection over doing the right thing, bureaucracy prevails and power is concentrated amongst a few - we feel we are in a ‘war-like’ zone. In these situations, camouflaging or hiding in plain sight is a good strategy.

Blind courage might not be the best route. Self-preservation, until we find an escape route is probably best. When brands are in crisis, they go very still, even retreating until the situation improves. People change companies, change teams, or bide their time until they find more conducive environments.

When we are in situations like the one at Twitter right now, it feels like the building is on fire. Better to try to survive while looking for an exit route. In these scenarios, quiet quitting might also be a good strategy.

But it is best to avoid prolonged existence in these environments.

Professor Sutton would agree.

3.1 Life and work are littered with assholes. Professor Bob Sutton at Stanford is not an asshole. Far from it. But he sure knows them.

He has written The No Asshole Rule, and The Asshole Survival Guide. (Must-read books for those who are struggling with bullies). Professor gives us 6 questions to diagnose the situation. Warns us to watch for ‘Asshole blindness’ - where we tell ourselves things are not as bad as they seem and we stick on. He also gives multiple strategies to deal with assholes. One of them is to hide in plain sight. Another is to quit.

Lastly, a sobering thought to round off this edition.

Be slow to label others as assholes, be quick to label yourself as one. -Prof. Bob Sutton